Saudis’ cheap oil gamble will cost us all dear !!!

Riyadh is determined to drive energy rivals out of business whatever the damage to the world

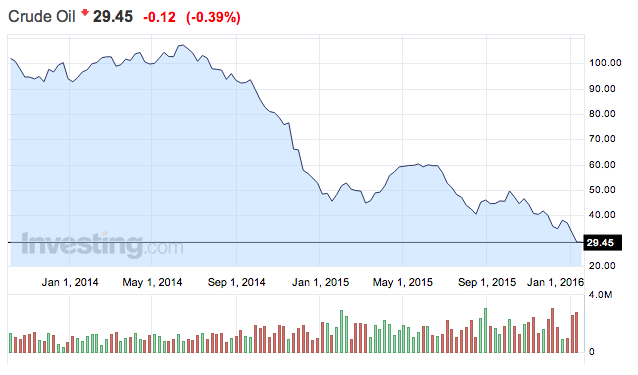

Oil prices since January 2014

Oil prices since January 2014

Traditionally cautious, the Saudi royal family has been sailing close to the

wind since King Salman came to the throne a year ago. The British diplomatic

establishment, with its love of deference and falconry (and eager arms

industry), has preferred to look the other way as the kingdom’s provocative

foreign policy and determination to drive down the price of oil threatens a

chain reaction that could destabilise much of the world. It took our allies

in Germany’s intelligence service to sound the alarm last month at Riyadh’s

new “impulsive policy of intervention”.

In Syria’s festering civil war, the Saudis back the “Army of Conquest”, an

Islamist umbrella group which includes the al-Qaeda affiliate the al-Nusra

Front. In Yemen, a Saudi-led coalition is waging war on the insurgent

quasi-Shia Houthi, on the pretext that they are merely cat’s paws of Iran,

whose influence Riyadh seeks to extrude, not just from the Arabian

peninsula, but the “Sunni Arab world” in general. Apart from deepening

Yemen’s humanitarian crisis, this foolish campaign has widened the anarchic

space available to al-Qaeda’s heirs.

King Salman has also been ramping up Saudi oil output, in the service of geopolitical as well as commercial goals. The aim was to cripple surging US shale production and to damage the rival economies of Iran and Russia, thereby allowing cheap Saudi oil to gain Asian and European market share. Crude prices have been driven below $30 a barrel — 70 per cent down on 2014’s highs. Despite the remarkable technical creativity of US shale drillers, the industry has $200 billion debt that their bankers worry could turn sour if oil prices remain this low. Oil majors around the world have cancelled about $400 billion worth of new exploration projects in the past 12 months. 65,000 jobs have gone in the North Sea alone.

As Iran emerges from diplomatic isolation, any bonus it hoped to reap on the international markets is cancelled by the low price of oil. Why invest the windfall created by the lifting of sanctions in ramping up production, as the oil ministry and most ordinary Iranians wish, when it could be spent on more foreign mischief-making by the Quds force of the Revolutionary Guard?

Although Iran’s ally Vladimir Putin has cunningly hedged his bets — offering Riyadh 16 nuclear reactors while selling S-300 missiles to Tehran — the Russian economy is tanking. Doctors, teachers and other essential workers increasingly face lay-offs and non-payment of salaries. More than 23 million restive Russians — more than a sixth of the population — now live on less than $179 a month, the official poverty benchmark.

But the political consequences of King Salman’s gamble go much deeper. Declining oil revenues have cast a light on the corrupt ties between state oil companies, big business and political parties, as alleged by the “Operation Car Wash” investigations into Petrobras and Dilma Rousseff’s ruling Workers’ Party in Brazil. Creaky regimes from Algeria to Venezuela which need oil (and gas) revenues to buy off domestic dissent have failed to persuade Opec to reverse Riyadh’s course. Venezuela’s President Maduro is under pressure to abandon the deal whereby he gives Cuba virtually free oil in return for doctors and secret policemen. Nigeria relies on oil sales for 70 per cent of state spending, so low prices will hamper President Buhari’s plans to tackle the Islamist insurgency of Boko Haram in the north. The authorities in Iraq cannot pay the troops fighting Isis. Fuel subsidies that have made bottled mineral water more expensive than fuel are up for review, from Egypt to the Gulf States, with the potential to trigger unrest in many Arab nations.

Ironically, international sanctions helped Iran adapt to the low oil price better than most Opec members. Oil and gas revenues account for a quarter of its budget, while 40 per cent comes from a taxation system modernised with western help and which this year will encompass the autarchic Revolutionary Guard for the first time.

The Gulf States, notably Saudi Arabia, have fewer options. That is why they have been dipping heavily into their sovereign wealth funds — the Saudi one fell from $730 billion to $640 billion last year — while selling off foreign assets and issuing their own bonds. The current Saudi budget also runs a 20 per cent deficit. JP Morgan calculates that these states will collectively liquidate $240 billion of overseas assets this year.

Since the new team in Riyadh cannot liberalise their institutions, and have failed to significantly diversify an economy whose waste of oil and gas is profligate already, Crown Prince Mohammed has made much of plans to privatise parts of Saudi Aramco, the huge national oil concern. This seems like a quick fix dreamt up by princely smart alecs to solve complex problems. The company’s books are opaque (as are its oil reserves) and especially its function in rewarding cadet branches of the House of Saud. As for the regime’s other wheeze of developing tourism to pre-Islamic heritage sites, good luck with that one when the Wahhabi clerical establishment ponder the ramifications of it.

The Saudis may be congratulating themselves about the havoc they have caused by keeping the oil price so low. But they should reflect that the House of Bush is no longer a power in the US, and that the combination of privatisations at home and warlike ventures abroad is not one that autocracies built on public largesse tend to survive.

Michael Burleigh is author of Small Wars, Far Away Places

Saudi Arabia's foreign minister just gave an utterly unconvincing explanation for the plunge in global oil prices

Oil is down to $28 a barrel, a drop in price that's going to have an untold and possibly disruptive impact on countries around the world and across the development spectrum.

An emerging conventional wisdom holds that Saudi Arabia, the world's second-largest oil producer — and largest that isn't under US and EU sanctions — could make the price plunge go away by dialing back its own 10.25 million-barrel-a-day output.

But Riyadh is choosing not to, according to this theory, in order to cut into the oil profits of Iran, Saudi Arabia's top geopolitical foe.

This is not a theory that the Saudi government would like to see advanced.

Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir pushed back against this narrative during a January 19 interview with CNN's Wolf Blitzer. He claimed that Saudi Arabia didn't want to cut production because it's worried about the consequences of what he believes would be an artificial price increase.

"The oil price is determined by supply and demand in the market, and there was an oversupply in the market because of overproduction in a number of countries that led to a drop in the price," al-Jubeir told Blitzer.

He added that a cut in production would effectively bail out the countries allegedly responsible for the price drop while only delaying the current, supposedly market-driven drop in price: "Saudi Arabia refused to cut its production in order not [to] support high producers, since that would have set a stage for a drop in prices and volume down the road ... What we're seeing now is the market price."

In short, he's saying that if Saudi Arabia cuts production, it will be just as guilty of price manipulation as all the countries that overproduced and got the world into this situation in the first place.

The Saudi foreign minister, whose government is effectively responsible for 13% of global oil output, also argued against using oil production as a political cudgel.

"If you try to manipulate it one way or another and you overshoot or undershoot, and you pay a tremendous price for it," al-Jubeir said.

There's a transparent problem with this entire line of argument, though.

The oil price is partially set by production and price targets set within the OPEC oil cartel, of which Saudi Arabia is the most influential member. OPEC hasn't changed production targets in spite of the price dip. Saudi Arabia's oil extraction is also largely the work of Saudi Aramco, a company owned by the Saudi state. The oil price is already subject to plenty of Saudi manipulation.

There's also an obvious tension in a Saudi government official simultaneously arguing that some countries are "high producers" and that oil has settled on a rational market price. If that were the case, Saudi Arabia might consider curtailing its production in order to account for high production in other countries. But the oil price isn't only set by the market.

It's overly simplistic to claim that the oil price is low just because of the Saudi-Iranian "cold war." Production is up in a lot of places, including the US. Riyadh is also paying a price for cheap oil, cutting public spending, introducing new taxes, and possibly privatizing a small percentage of Saudi Aramco, the Saudi state oil concern and possibly the most valuable company on Earth. Saudi Arabia probably has a range of non-Iran-related motives for producing as much oil as it does.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia isn't quite as harmed by low prices as other countries. As The Economist notes, Saudi Arabia's break-even price on oil is a mere $12 a barrel. Iran's is at nearly $30, and the US is nearly $70. Saudi Arabia has 16% of the world's proven oil reserves and can raise revenue through selling off relatively insignificant percentages of Saudi Aramco.

Saudi Arabia is better positioned to absorb a protracted price drop than many other oil producers. Prices might be low because the country can afford to keep them low. And politically, Saudi Arabia is still arguably the most influential and militarily powerful country in the Arab world even with the price drop, and may only see its importance increase as it organizes its allies to counter Iran's post-nuclear deal rise in influence.

Al-Jubeir said that Western speculation about Middle Eastern oil production was a "conspiracy theory." But he's hardly more credible in claiming that "the market" is dictating Saudi production totals.

Comments