Mark Hollis Obituary

Mark Hollis Obituary

So long out of the public eye and now lost to us. Thank you for the musical experiences

Rest in Peace

Rest in Peace

In 1982, when his synth-pop band Talk Talk were making a mark on the charts with the singles Talk Talk and Today, Mark Hollis said: “I want to write stuff that you’ll still be able to listen to in 10 years’ time.” Nearly 40 years later, Hollis, who has died aged 64, has left a musical legacy that seems set to last indefinitely.

Although Hollis hated the way Talk Talk were packaged by their label EMI in white suits and black ties and bundled in with New Romantics such as Duran Duran (whom they supported on tour) or Ultravox, even his early songs still stand up to critical scrutiny. Talk Talk, a UK No 23 in 1982, and It’s My Life, which reached 46 on the UK chart in 1984 and 13 when reissued in 1990, are punchy, melodic and tightly focused. Talk Talk’s debut album The Party’s Over climbed to 21 in Britain, but Hollis was dreaming of greater and grander things. The second album, It’s My Life (1984), found the group broadening its musical scope and instrumental palette, and while it reached only 35 in the UK, it cracked the US Top 50 and scored highly on charts across Europe, with European audiences also taking a shine to the single Such a Shame.

The group finally cut all ties with the synthesiser era with The Colour of Spring (1986), a powerful and coherent set of songs which delivered the major hit Life’s What You Make It and a slightly lesser hit with Living in Another World. They typified the album’s mix of powerful, spacious rhythms with carefully wrought instrumental colours, topped by Hollis’s pained and yearning vocals. By now Hollis was writing all the material with Tim Friese-Greene, who had been brought aboard for the It’s My Life album as producer and keyboard player. The album was a hit internationally.

However, apart from the compilation Natural History: The Very Best of Talk Talk (1990), which reached No 3 in the UK and sold a million copies worldwide, this would prove to be the high-water mark of Talk Talk’s chart success. Henceforth Hollis would take the group (comprising its original drummer Lee Harris and bass player Paul Webb, and with Friese-Greene as a regular contributor) into boldly experimental territory, creating music that would prove influential on many other artists, but was anathema to record companies looking for hit singles and platinum discs.

Hollis was born in Tottenham, north London, and attended Tollington grammar school in Muswell Hill (now Fortismere school). Hollis was always cagey about discussing his life and background, but did say he took a course in child psychology at Sussex University which he failed to complete. His move into a musical career was greatly influenced by his older brother Ed, who was writer and producer for the Canvey Island pub rockers Eddie and the Hot Rods. Ed’s own musical tastes were eclectic, and he encouraged Mark to dip a toe into everything from free jazz to prog rock and American garage bands. The punkish spirit of the era could be discerned in Mark’s first band, the Reaction, who released the single I Can’t Resist in 1978.

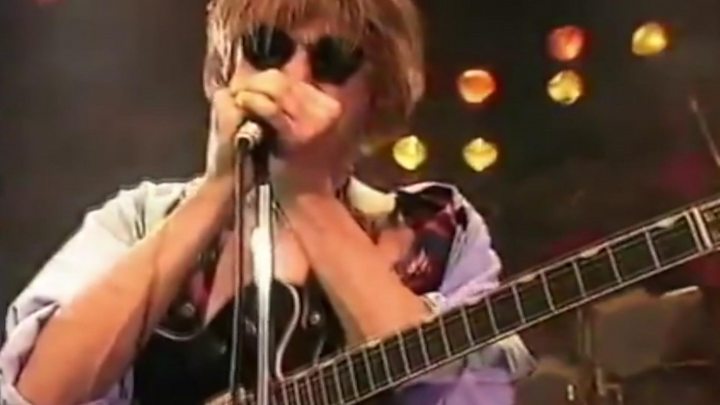

Mark Hollis, second from left, with, from left, the keyboard player Simon Brenner, drummer Lee Harris and bassist Paul Webb, in a 1982 publicity shot for Talk Talk - Hollis was said to hate the way EMI packaged the band in white suits and black ties.

Ed also influenced the line-up of the fledgling Talk Talk, helping Mark to find Webb, Harris and the keyboard player Simon Brenner, who all hailed from the Southend-on-Sea area. Their deal with EMI came about after the A&R man Keith Aspden heard a demo tape they had sent to Island Music, which impressed Aspden so much that he left his previous job to become their manager. EMI put the group together with the producer Colin Thurston, who had worked with David Bowie, the Human League and Duran Duran, and they set to work on Talk Talk’s debut album.

The success of The Colour of Spring meant that Talk Talk had a bigger budget to play with on the follow-up, Spirit of Eden (1988), but Hollis’s musical thinking was now geared towards Debussy, Erik Satie and Ornette Colemanrather than other pop or rock acts. Spirit of Eden, with its startling musical textures, sudden changes of pace and interludes of silence, was as much a modern classical album as a pop record. Though many critics hailed it as a masterpiece and it reached the UK Top 20, EMI were frustrated at its lack of commercial selling points. After months of legal wrangling, band and label parted company.

With the band now reduced to Hollis and Harris, with Friese-Greene producing and playing keyboards, Talk Talk’s final album Laughing Stock (1991) was released by Polydor’s Verve label, and pushed the musical envelope a little further (it began with 18 seconds of silence). Though sombre and uncompromising, it reached 26 in the UK, a reflection perhaps of the strange, lingering allure of pieces such as Taphead and Ascension Day.

The group now disbanded, with Hollis claiming that he wanted to focus on family life with his wife Flick, a teacher, and their two sons. Having been living in rural Suffolk, Hollis moved to Wimbledon, south-west London, in 1998, the same year he released his only solo album, entitled Mark Hollis. If anything even more sparse and haunted than what preceded it, it seemed a fitting coda to Hollis’s career, from which he had now apparently retired. Musicians including Tears for Fears, Radiohead, Elbow’s Guy Garvey and Steve Wilson of Porcupine Tree have acknowledged Talk Talk’s influence, while No Doubt’s 2003 version of It’s My Life was a hit in the US and Britain. A tribute album, Spirit of Talk Talk, was released in 2012.

Hollis did break cover fleetingly. As well as making guest appearances on Unkle’s album Psyence Fiction and Phill Brown and Dave Allinson’s AV1 (both 1998), he popped up on Anja Garbarek’s album Smiling & Waving (2001) to play bass guitar and melodica, and in 2004 collected a BMI award as writer of It’s My Life. In 2012 he composed a piece of music for Kelsey Grammer’s TV drama Boss.

He is survived by his wife and sons.

• Mark David Hollis, singer, musician and composer, born 4 January 1955; died 25 February 2019

Figures from the world of music have paid tribute to Mark Hollis, frontman of the band Talk Talk, following his death at the age of 64.

Hollis’s manager, Keith Aspden, confirmed the news to NPR. “I can’t tell you how much Mark influenced and changed my perceptions on art and music. I’m grateful for the time I spent with him and for the gentle beauty he shared with us.”

With Hollis as its singer and creative mastermind, the group made a name with 1980s hit singles such as It’s My Life, Today, Talk Talk and Life’s What You Make It. They progressed to albums like Spirit of Eden, which was hailedas a “masterpiece”, and Laughing Stock.

His cousin-in-law Anthony Costello tweeted on Monday: “RIP Mark Hollis. Cousin-in-law. Wonderful husband and father. Fascinating and principled man. Retired from the music business 20 years ago but an indefinable musical icon.”

Talk Talk’s bassist Paul Webb, aka Rustin Man, paid tribute to Hollis on Instagram. “I am very shocked and saddened to hear the news of the passing of Mark Hollis,” he wrote. “Musically he was a genius and it was a honour and a privilege to have been in a band with him. I have not seen Mark for many years, but like many musicians of our generation I have been profoundly influenced by his trailblazing musical ideas.”

In an interview with Q’s backpages at the time, later republished in the Guardian, Hollis expressed awareness that he could be “a difficult geezer” but that was because he refused to “play that game” that came with the role of musician in the spotlight.

“It’s certainly a reaction to the music that’s around at the moment, ‘cos most of that is shit,” Hollis also said of Spirit of Eden. “It’s only radical in the modern context. It’s not radical compared to what was happening 20 years ago. If we’d have delivered this album to the record company 20 years ago they wouldn’t have batted an eyelid.”

Hollis released his first and only solo album, also called Mark Hollis, in 1998. When asked about his decision not to tour anymore or maintain a public persona, he said: “I choose for my family. Maybe others are capable of doing it, but I can’t go on tour and be a good dad at the same time.” He later retired from the music industry, and was little heard from publicly. An article about him last year was headlined “How to disappear completely.”

His last known music was created for TV drama Boss starring Kelsey Grammer and TI.

Hollis’ influence has often been referenced by musicians, including Elbow’s Guy Garvey. “Mark Hollis started from punk and by his own admission he had no musical ability,” he told Mojo. “To go from only having the urge, to writing some of the most timeless, intricate and original music ever is as impressive as the moon landings for me.” Bands including Broken Social Scene, The The, Doves and Mansun have all paid tribute on Twitter.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/aug/28/from-rocks-backpages-talk-talk

Talk Talk: 'You should never listen to music as background music' – a classic interview from the vaults

It’s 25 years since Talk Talk released their masterpiece Spirit of Eden. In this classic Q interview – taken from Rock’s Backpages, the home of music writing – they discuss the making of the album, and how they fought against compromise

"No," says Mark Hollis stubbornly, he will not look directly into the camera as this, apparently, is compromise tantamount to soul-selling.

"No," he says, he doesn't see why he should have to explain his music to anyone. It speaks, he reasons – dusting down the superannuated cliché – for itself.

"No," he explains, he will not read this article. He's been stitched up in the press so many times before, it will probably happen again.

The trouble is that Mark Hollis and his band, Talk Talk, have just released their fourth LP, Spirit of Eden, and there are promotional duties to reluctantly perform. Had Spirit of Eden been an unremarkable pop record, none of this would have been necessary. However, this is not the case. For Spirit of Eden is a quite remarkable, possibly even significant work that makes their powerfully dense and emotional 1986 set, The Colour of Spring, sound not unlike a Rubettes demo.

It is the fourth stage in Talk Talk's intriguing metamorphosis from the quirky singles band who appeared at a time when Duran Duran were considered the ultimate role model, to a collective of almost painfully intense musicians who are much given to name-checking Satie, Bartók ("a great geezer") and Debussy.

Mark Hollis, in what occasionally seems to be a strained attempt to appear enigmatic, is keen to dismiss his past, his flunked university degree in child psychology, his five years of fruitless toil with punk band the Reaction, even the "diabolical" treatment of Talk Talkwhen they first hopped aboard the pop carousel in 1982.

Hollis's co-writer and producer, Tim Friese-Greene, is similarly reticent to reminisce. "As far as I'm concerned," he says, "this began in 1984 with It's My Life and nothing else is particularly relevant."

Both Hollis and Friese-Greene will happily discuss "vibe", "feel", and how they achieved Spirit of Eden's brittle and brooding atmospheres, harsh dynamic extremes and constant mesmeric pulse. But amid heavy-shouldered shrugs and staunchly monosyllabic pleas of ignorance, neither seems vaguely interested as to who will buy the record, how it will be made available or the effect it will have. They leave this to Tony Wadsworth, Capitol and Parlophone Records' general manager who is responsible for the marketing of among others Queen, Pet Shop Boys and Morrissey.

"Talk Talk are not your ordinary combo and require sympathetic marketing," Wadsworth explains diplomatically. "They're not so much difficult as not obvious. You've just got to find as many ways as possible to expose the music. The standard marketing route is whack out a single, try to chart the single, and then hopefully on the strength of that, sell some albums. With the way the media is angled, the room you've got to expose adult music – for want of a better term – is very restricted. We've got to do what I believe to be a very heavy campaign on Talk Talk. We've got to go out very bullishly and tell people that this is an album for 1988. That will be the sales pitch – An Album for 1988."

Similarly, Spirit Of Eden could be An Album for 1972. It boasts just six songs, three of which seamlessly comprise one side of the LP. No one track appears to exceed 15 beats per minute. The instrumentation is predominantly acoustic, and Hollis's anguished Steve Winwood-registered voice seldom rises above a whisper. The lyrics abstractly embrace such thigh-slapping subject matter as moral decline, drug addiction and that perennial party-starter, death. Commercially, it is hard to envisage the album as "a goer".

"When I heard it first in its finished form," says Wadsworth, "I thought, 'Mmm, this is interesting,' then got into it very quickly. Technology aside, it could have been made 20 years ago. I see it as even earlier than that. It's like a cross between classical music and jazz with a modern perspective. I don't see it as directly related to acid house but I see the phenomenon as having the same sorts of roots. There's common interests. They're both free-form with an insistent rhythm. I think it'll be well received. People are looking something a little more open-minded."

"Pace is of the essence," says Friese-Greene of the album's refusal to break into a brisk stroll, "even if it is a pace that approaches vanishing point at times. The more relaxed the pace, the more importance everything that happens assumes. You have to be careful and not overstep the line from being relaxed to being tedious and I think we've kept on the right side of that."

"The dynamics are a little bit hard to take at first," he continues. "There were times during the mixing when I thought, 'I'm not sure about this,' but it scrapes through. Again it had to strike the right note between intensity and irritation. But we're not being naive about it. Some people could definitely be put off by the pace of it or the level of intensity and if people are uncomfortable with that maybe, with respect, they should listen to something else."

Talk Talk's image has, throughout their six-year career, moved nonchalantly between the poor and the non-existent. Despite having been "styled" upon their signing to EMI ("We were under terrible pressure," says Hollis. "It's a very ugly thing. Things went down that I was very unhappy with. It was ridiculous. Disgusting. But I don't regret it; they just made me more adamant never to get caught like that again"), the band soon went their own sartorial way, growing unkempt normal-to-greasy hair, wearing clothes that could only have been bought with a War on Want charge-card and sporting footwear which invited the expression "hush puppies".

"The image," laughs Tony Wadsworth, "or lack of it, doesn't bother you when you have Pink Floyd on your label. Look at Dire Straits. Hardly the most fashion-conscious group, and yet they're the biggest band in the world. Talk Talk have always seen that side of things as a distraction from the music."

Hollis's rocky relationship with the press swiftly gained him a reputation as being something of a surly, self-obsessed character.

"You can understand that, though," argues Friese-Greene. "When Mark started up he was sometimes doing 12 interviews a day. That just drives you mad after a while and you have to do something, wind the journalist up or whatever, to remain sane."

"It doesn't worry me that Mark is seen as uncooperative," says Wadsworth. "It worries me more that we might put him in a situation that might compromise him. I can fully understand that a serious artist like Mark does not want to go on Saturday morning children's television and have 10 gallons of sludge poured over him and then be presented with a giant inflatable banana. I mean, this man is a father!"

Mark Hollis is aware that he is perceived as "a difficult geezer" at times. This, he says, is because he won't "play that game" of handshaking and pleasantry-exchanging. But rather than giving the impression of being a terse, rapier-tongued weasel, he comes over more as a nervous, pensive individual with a few ideas of great import to unleash upon the populace.

He is motivated, he says, by the need to make great and "increasingly personal" music. "Money is not a worry," he sniffs. "I've got all the money I need."

Indeed, the sales of Talk Talk's three LPs to date have been mightily respectable. The Party's Over – promoted by two hit singles and a sizable American tour supporting Elvis Costello – sold over a quarter million copies; their second album, It's My Life, went gold in every European country except Britain, selling particularly well following exhaustive live work, in Italy ("I couldn't tell you why that was," mutters Hollis. "You'd have to ask everyone in Britain and then everyone in Italy, I suppose"); The Colour of Spring aided and abetted by the top 20 single Life's What You Make It, also went gold. Split the net profits and divide between Hollis, Friese-Greene, drummer Harris and bass player Paul Webb who comprise the group's – hey! – floating nucleus and it doesn't take long to fathom out how Hollis can afford to sit in his Suffolk village rectory and "just do music, really". Ask Tim Friese-Greene if Hollis is the most boring person in the world, he will pause and reply, "No … he's probably the second most boring person in the world, because, according to him, there is no one more boring than me."

One wonders how they mustered the energy to produce such a reaction-provoking record. "Well, it's certainly a reaction to the music that's around at the moment, 'cos most of that is shit," deadpans Hollis. "It's only radical in the modern context. It's not radical compared to what was happening 20 years ago. If we'd have delivered this album to the record company 20 years ago they wouldn't have batted an eyelid."

Would you recommend any particular situation in which to listen to it?

"Late at night definitely. In a very calm mood with no distractions."

You don't think it would make rather pleasant background music at, say, a dinner party?

"No I don't. Maybe after the dinner party. But you have to give it all your attention. You should never listen to music as background music. Ever."

Talk Talk's original plan of action was not to release a single or a video from the album. Neither did they intend to tour. Although they still won't be playing live ("People would just want to hear the songs as they are on the album and for me that's not satisfying enough," Hollis frowns), they have since reconsidered, with a little record company pressure, and edited the track I Believe In You down to airplay length.

"It's purely in order to help the record company promote this album," says Hollis. "Purely that." He has also, now, recorded a promotional video to accompany the single.

"I really feel that was a massive mistake." he grimaces. "I thought just by sitting there and listening and really thinking about what it was about, I could get that in my eyes. But you cannot do it. It just feels stupid. It was depressing and I wish I'd never done it."

"See," he spits, "that's what happens when you compromise."

Talk Talk - The spirit of Eden, side 1 (1988)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i-uCvlslH-s

Obituary: Talk Talk's Mark Hollis

"Our songs are about tragedy... Human tragedy."

Talk Talk may have been lumped together with synth-pop bands like Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet.

But singer Mark Hollis, who has died after a short illness aged 64, possessed a lyrical depth and musical curiosity that set him apart.

By their fourth album, Spirit of Eden, he'd abandoned pop formulas in favour of ambient textures and jazz structures - setting a blueprint for bands who want to outgrow their origins.

From the outset, Hollis's tastes were eclectic. His first record was the Northern Soul classic Everlasting Love, which he bought at the age of 12, while his first concert was David Bowie.

Speaking to Record Mirror in 1982, he cited his main influences as Burt Bacharach and counterculture icon William Burroughs.

He also said the best live show he'd ever seen was a performance of Shostakovich's Symphony No 10 at London's Royal Festival Hall.

Those facts aside, little is known about Hollis's early life - mainly because of his tendency to tell tall tales in interviews.

Born in Tottenham in north London in 1955, he told one journalist he'd dropped out of school before his A-Levels, while informing another he had studied child psychology at the University of Sussex.

Upon leaving education, he claimed to have worked as a laboratory technician - but music was always his first love.

"I could never wait to get home and start writing songs and lyrics" he told Kim magazine in 1983.

"All day long I'd be jotting ideas down on bits of paper and just waiting for the moment when I could put it all down on tape."

Duran comparisons

Hollis formed his first band, The Reaction, in 1977 and recorded a demo for Island Records that included a song called Talk Talk Talk Talk.

The group split after one single, after which Hollis intended to pursue a solo career. After writing a new batch of songs, he recruited Paul Webb, Lee Harris and Simon Brenner to help him flesh out the arrangements in the studio.

"But we liked what we were doing so much that we decided to throw every penny we had into hiring a rehearsal room and practicing to go out and play in the clubs," he said.

The quartet soon had a name, Talk Talk, and a record deal with EMI Records, who hoped to mould them into another Duran Duran.

The company even hired that band's producer, Colin Thurston, to work on their first two singles, Mirror Man and Talk Talk.

But the band were keen to shake off the "New Romantic" tag, even dismissing their keyboard player to make it clear they weren't a synth-pop band.

"It gets tiring to listen to the Duran comparisons" Hollis told Noise! magazine at the time. "I can't hear it myself.

"I get depressed about the whole thing [because] kids ought to know about music, not image."

The band deliberately took a year to craft their second album, It's My Life, and even recorded animal noises at London Zoo for the title track.

The video for the song was compiled from rushes of the David Attenborough series Life on Earth.

It's My Life went on to become Talk Talk's biggest hit. A cover by No Doubt reached the US Top 10 in 2003.

The year 1986 saw the release of The Colour of Spring, which hinted at their musical ambitions.

Based on the strength of the singles Life's What You Make It and Give It Up, it became the band's biggest album to date.

A year later, Talk Talk settled into an abandoned Suffolk church to begin working on their fourth LP.

When they emerged 14 months later, it was hard to believe it was the same band.

Drawing on ambient textures, jazz-like arrangements and stunning orchestral arrangements, Spirit of Eden is a meditative, melancholy six-song suite that's as downbeat as it is breathtaking.

"It's an engrossing, modern 'head' album, the kind of recording that Pink Floyd never became heavy enough to make," said The Times in a typically enthusiastic review.

"I'd never heard music that dynamic while being organic," wrote Elbow's Guy Garvey, who named Spirit of Eden his favourite album in a recent edition of Q Magazine.

"It's such a brave record. To this day, I can hear its influence."

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

The record performed poorly with audiences, however. EMI deleted it after three months and promptly dropped Talk Talk from their roster.

Re-signing to Polydor, the band released one further album - the equally ambitious Laughing Stock - before quietly dissolving.

"There was no big split," Hollis later told The Times. "By the end, everything was so loose that walking away didn't seem like a wrench. We'd reached an end point."

Hollis waited eight years before releasing his first, and only, solo album. Self-titled, nuanced and delicate, it was recorded with just two of microphones strategically placed to capture the musicians' every inflection, from gently caressed guitar strings to the creaking of their chairs. It ends with two minutes of analogue tape hiss.

Perhaps he was always travelling towards silence. "Before you play two notes, learn how to play one note, and don't play one note until you've got a reason to play it," he said in 1998, shortly before retreating from public life altogether.

But there's something uniquely inspiring about a musician who puts a full stop on their career.

There are no second-rate comeback albums or awkwardly staged reunions to taint Talk Talk's legacy. And that's presumably the way Hollis wanted it.

Comments